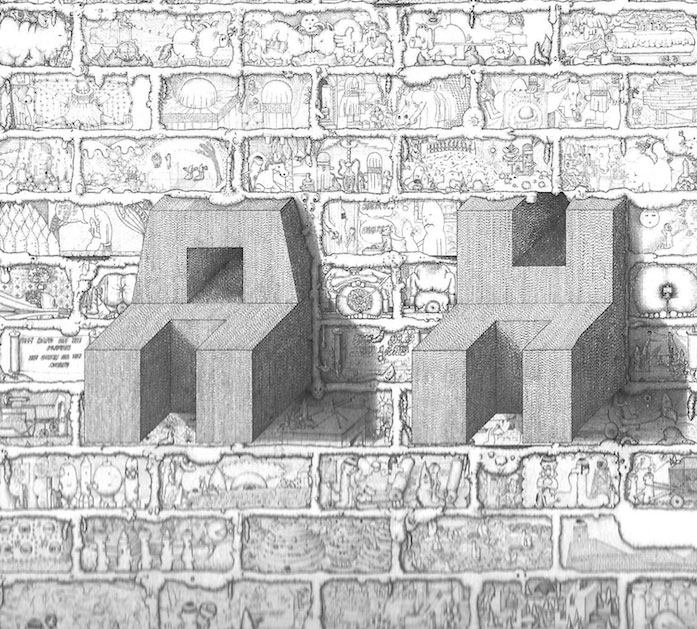

Do Ho Suh

Considering the blurred distinction between public and private realms and severe penetration of private world into public domain, our summer exhibitions and workshops intend to question and highlight the importance of "domesticity" and our contemporary urge to carry our domestic qualities and rituals with us as we exit our private domain.

One of our exhibition was a review on artworks by Do So Suh, a South Korean artist.

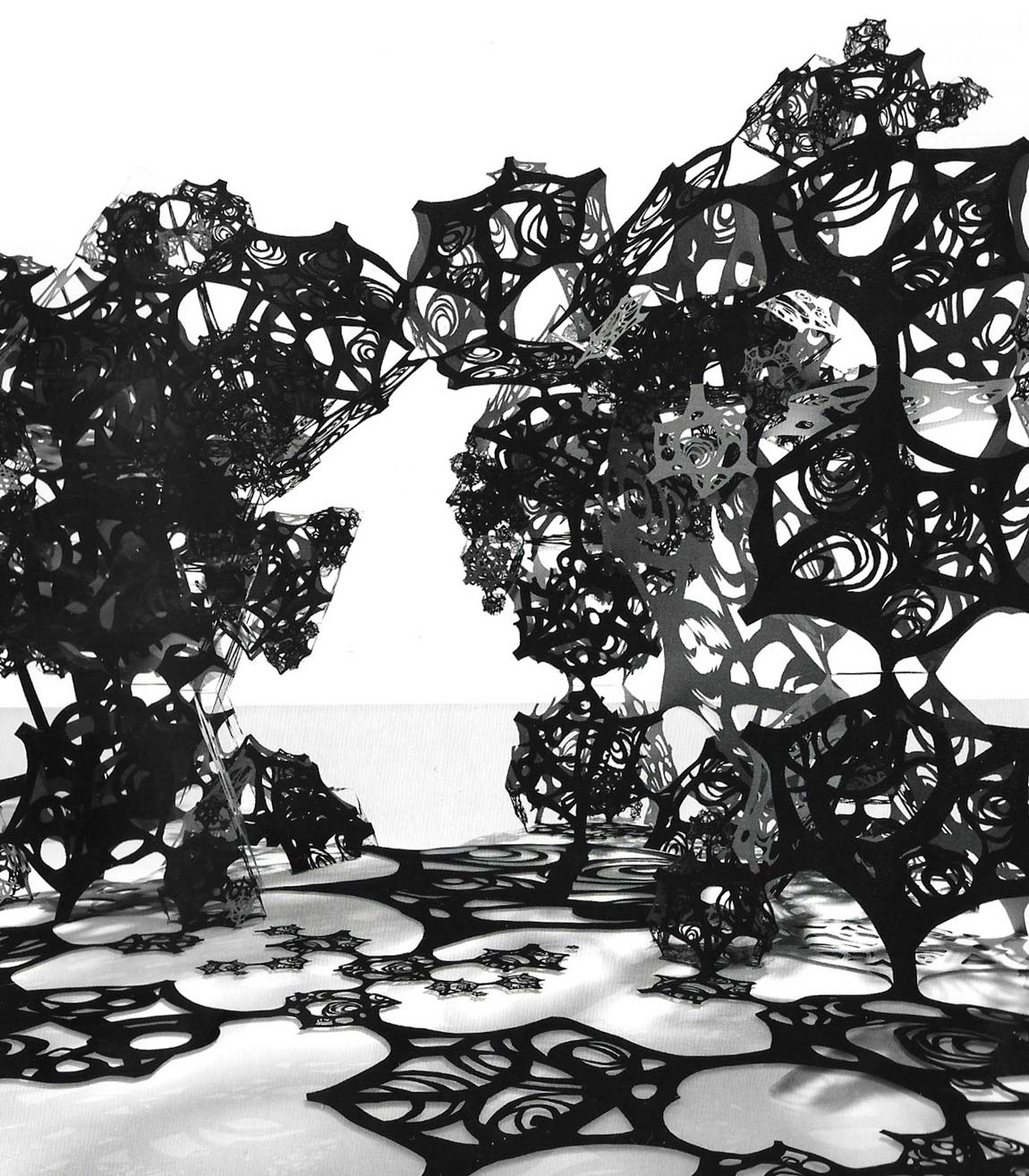

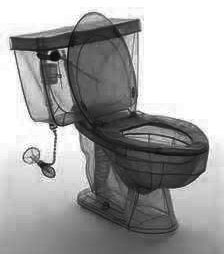

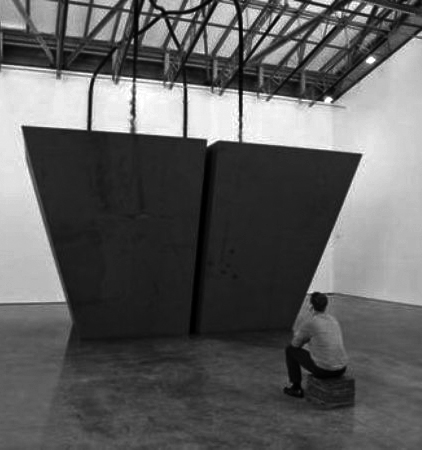

Architectural settings and abstracted figures inspired by the artist’s biography serve as the central tenets of Do Ho Suh’s practice, highlighting the porous boundary between public and private space as well as notions of global identity, space, nomadism, memory, and displacement. Born in Seoul, South Korea, Suh is informed by his personal experiences in his work, particularly his move from South Korea to the United States in 1991, as well as the specific domestic spaces where he has lived, including his childhood home (a traditional hanok-style Korean house), a house in Rhode Island where he lived as a student, and his apartment in New York. Transparency, or the oscillation between opacity and visibility, appears throughout much of the artist’s work, evoking the layering of space and intermediate areas in Korean architecture. The figure also looms large, waiting in the wings, appearing throughout his work in abstracted or symbolic forms. Suh first began rendering domestic structures in 1994, an impulse turned into life’s work. These have been manifested, on one hand, in iterations of large-scale house sculptures—also riffs on his past and present family homes—variously bisected to show their interiors, teetering precariously atop or wedged between structures, or displayed in a gallery as if they have crashed through the ceiling, cast down by Dorothy’s tornado. Suh also weaves transparent structures made of monochrome polyester, at once luminous, architectural, and ephemeral, inviting viewers to wander through their dreamlike interior passageways (which might be replete with toilets and light switches). These transplanted homes are playful and imaginative but also deeply melancholy in their manifestation of disorientation: as impressions of the many residences in which Suh and his family have lived, they testify to the global and poignantly elusive nature of “home” as seen through the artist’s eyes.

Considering the blurred distinction between public and private realms and severe penetration of private world into public domain, our summer exhibitions and workshops intend to question and highlight the importance of "domesticity" and our contemporary urge to carry our domestic qualities and rituals with us as we exit our private domain.

One of our exhibition was a review on artworks by Do So Suh, a South Korean artist.

Architectural settings and abstracted figures inspired by the artist’s biography serve as the central tenets of Do Ho Suh’s practice, highlighting the porous boundary between public and private space as well as notions of global identity, space, nomadism, memory, and displacement. Born in Seoul, South Korea, Suh is informed by his personal experiences in his work, particularly his move from South Korea to the United States in 1991, as well as the specific domestic spaces where he has lived, including his childhood home (a traditional hanok-style Korean house), a house in Rhode Island where he lived as a student, and his apartment in New York. Transparency, or the oscillation between opacity and visibility, appears throughout much of the artist’s work, evoking the layering of space and intermediate areas in Korean architecture. The figure also looms large, waiting in the wings, appearing throughout his work in abstracted or symbolic forms. Suh first began rendering domestic structures in 1994, an impulse turned into life’s work. These have been manifested, on one hand, in iterations of large-scale house sculptures—also riffs on his past and present family homes—variously bisected to show their interiors, teetering precariously atop or wedged between structures, or displayed in a gallery as if they have crashed through the ceiling, cast down by Dorothy’s tornado. Suh also weaves transparent structures made of monochrome polyester, at once luminous, architectural, and ephemeral, inviting viewers to wander through their dreamlike interior passageways (which might be replete with toilets and light switches). These transplanted homes are playful and imaginative but also deeply melancholy in their manifestation of disorientation: as impressions of the many residences in which Suh and his family have lived, they testify to the global and poignantly elusive nature of “home” as seen through the artist’s eyes.