The delirium of Past and Present

The 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture was held under the main title of Fundamentals with the subcategory of Absorbing Modernity: 1914 – 2014 in the national pavilion section. For the first time, Iran officially participated under the latter section.

Iran’s pavilion titled Instant Past, curated by Azadeh Mashayekhi, Ali Farivar Sadri and Shabnam Hosseini, and with the relative support of the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development was on public display for six months. The exhibition was well received in the media, unfortunately however, due to various issues and a great deal of side stories that is not the place to expand on in this text, what was presented did not fulfill the wishes of the curators. The current exhibition has created an opportunity to review and complete the research without the government sector’s oversight.

In addition to exploring the inclination of Iranian architects to search the past, which was also demonstrated in the initial presentation, this exhibition investigates their penchant for the architecture of their contemporary world. It also takes into consideration the tension and the coexistence of the two different tendencies. Therefore, the title of the previous exhibition has changed to The Delirium of Past and Present. The original text has been rewritten. Several works were eliminated and some were added. Additionally, the film that was previously presented was unrelated to the topic and the curators did not fully approve of it. The current slide show is more on par with the goals of this research.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Kamran Adl whom without his remarkable photos this exhibition could not have been possible, Alireza Seyyed Ahmadian who aided me in understanding the concept of modernity, Arash Tabibzadehnouri whose guidance in selecting and preparing the documents was illuminating, Babak Mofidi who meticulously edited the current exhibition statement and Pedram Harbi whom the graphic presentation of the exhibition is the fruit of his tireless effort

Ali Farivar Sadri

+++

Modernity and Modernization are two different concepts. The concept of modernity belongs to a specific period in European history that could not have been embedded in any other region. The formation of modernity is rooted in the rational approach of those in the latter day against the oral approach of those who came before. The rational tradition is one that builds the present based on the critique of the past and in which, what is considered contemporary would be critiqued by those who come after. The progress of the European civilization is rooted in a tradition that emerged from a history, while modernization is outlining development schemes in Lands far away from Europe’s wheel of history. Modernization is the process of susceptibility of lesser-developed societies to more developed societies.

During the Qajar era, after the defeat to Russia (1803-1828), Iran suddenly encountered a world developed and unknown. The momentum sparked by the defeat was the initiation into modernization in Iran, which was simultaneously followed by resistance here and there. From then on, Iranians observed foreigners with awe and obsession with the new. They desired to become completely European yet the feeling of backwardness lured them towards restructuring the past, constructing a national identity and the creation of the concept of Westoxification in the hope of regaining their lost place. Iran’s contemporary history drifts between these two tendencies.

Iranian architects were not immune to this tension: at times their obsession with the new compelled them to copy images of the foreign and other times their uneasy conscious of backwardness leaned them towards becoming followers of the past. The history of Iran’s contemporary architecture is a range of experiences that grapple with these two inclinations.

Meanwhile, what is missed is formulating authentic theories of architecture with a look to the future, understanding the world today without awe and writing one’s own history without an uneasy conscious.

The 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture was held under the main title of Fundamentals with the subcategory of Absorbing Modernity: 1914 – 2014 in the national pavilion section. For the first time, Iran officially participated under the latter section.

Iran’s pavilion titled Instant Past, curated by Azadeh Mashayekhi, Ali Farivar Sadri and Shabnam Hosseini, and with the relative support of the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development was on public display for six months. The exhibition was well received in the media, unfortunately however, due to various issues and a great deal of side stories that is not the place to expand on in this text, what was presented did not fulfill the wishes of the curators. The current exhibition has created an opportunity to review and complete the research without the government sector’s oversight.

In addition to exploring the inclination of Iranian architects to search the past, which was also demonstrated in the initial presentation, this exhibition investigates their penchant for the architecture of their contemporary world. It also takes into consideration the tension and the coexistence of the two different tendencies. Therefore, the title of the previous exhibition has changed to The Delirium of Past and Present. The original text has been rewritten. Several works were eliminated and some were added. Additionally, the film that was previously presented was unrelated to the topic and the curators did not fully approve of it. The current slide show is more on par with the goals of this research.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Kamran Adl whom without his remarkable photos this exhibition could not have been possible, Alireza Seyyed Ahmadian who aided me in understanding the concept of modernity, Arash Tabibzadehnouri whose guidance in selecting and preparing the documents was illuminating, Babak Mofidi who meticulously edited the current exhibition statement and Pedram Harbi whom the graphic presentation of the exhibition is the fruit of his tireless effort

Ali Farivar Sadri

+++

Modernity and Modernization are two different concepts. The concept of modernity belongs to a specific period in European history that could not have been embedded in any other region. The formation of modernity is rooted in the rational approach of those in the latter day against the oral approach of those who came before. The rational tradition is one that builds the present based on the critique of the past and in which, what is considered contemporary would be critiqued by those who come after. The progress of the European civilization is rooted in a tradition that emerged from a history, while modernization is outlining development schemes in Lands far away from Europe’s wheel of history. Modernization is the process of susceptibility of lesser-developed societies to more developed societies.

During the Qajar era, after the defeat to Russia (1803-1828), Iran suddenly encountered a world developed and unknown. The momentum sparked by the defeat was the initiation into modernization in Iran, which was simultaneously followed by resistance here and there. From then on, Iranians observed foreigners with awe and obsession with the new. They desired to become completely European yet the feeling of backwardness lured them towards restructuring the past, constructing a national identity and the creation of the concept of Westoxification in the hope of regaining their lost place. Iran’s contemporary history drifts between these two tendencies.

Iranian architects were not immune to this tension: at times their obsession with the new compelled them to copy images of the foreign and other times their uneasy conscious of backwardness leaned them towards becoming followers of the past. The history of Iran’s contemporary architecture is a range of experiences that grapple with these two inclinations.

Meanwhile, what is missed is formulating authentic theories of architecture with a look to the future, understanding the world today without awe and writing one’s own history without an uneasy conscious.

-

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 6 (Correspondences)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 6 (Correspondences) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 5 (Publications)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 5 (Publications) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 4 (Photography)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 4 (Photography) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 3 (Domestic Objects)

-

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 2 (Interior Architecture)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 2 (Interior Architecture) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 1 (Architecture & Urban Design)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 1 (Architecture & Urban Design) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 0 (Introduction)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 0 (Introduction) -

No Fixed Adobe

No Fixed Adobe -

GEOtube

GEOtube -

Five Field Play Structure

Five Field Play Structure -

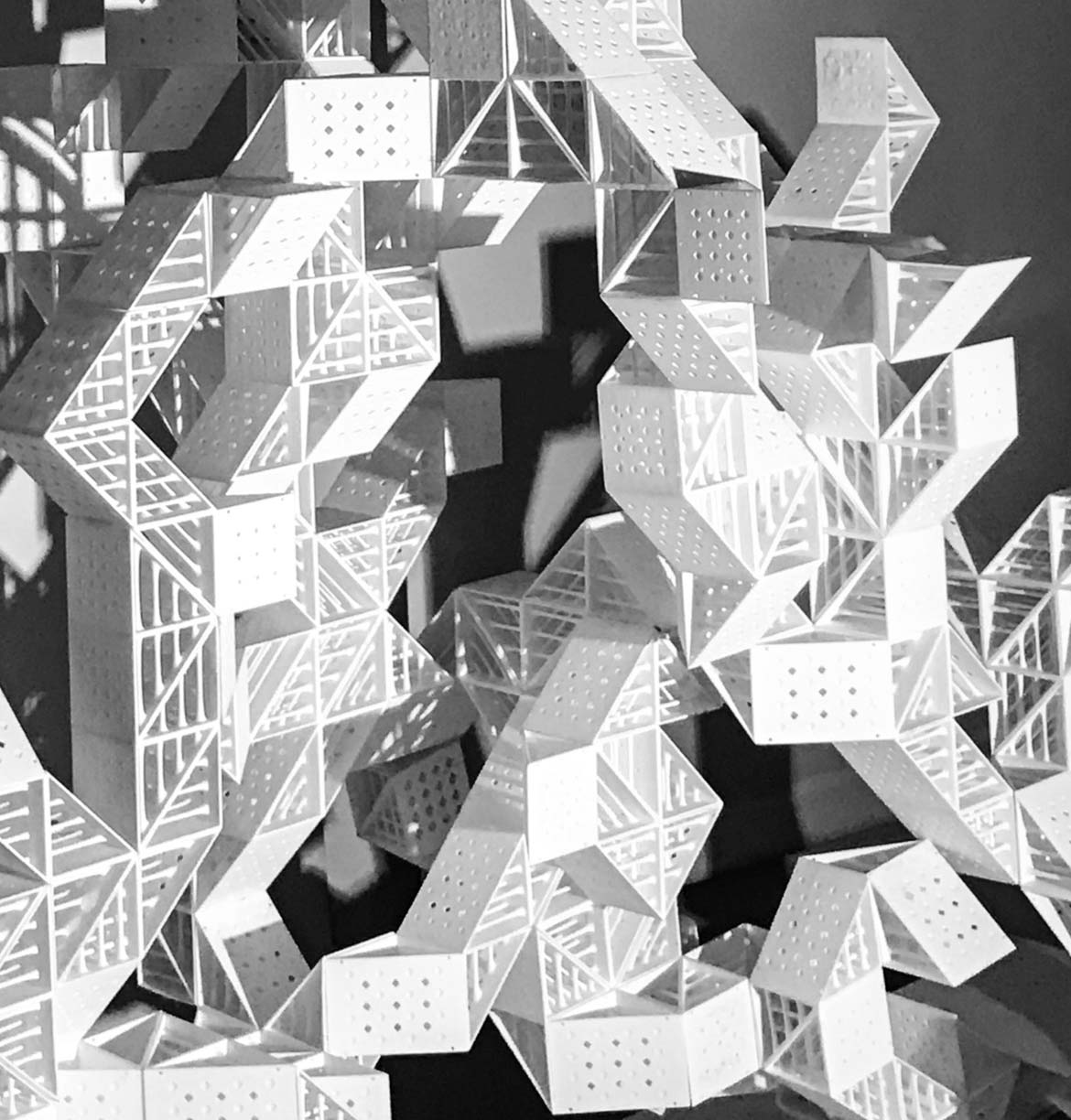

DNAted

DNAted -

Abandoned Qanats of Tehran

Abandoned Qanats of Tehran -

Bathroom Patterns

Bathroom Patterns -

Recycling Socialism

Recycling Socialism -

The delirium of Past and Present

The delirium of Past and Present