Sogol Kashani & Joubeen Mireskandari

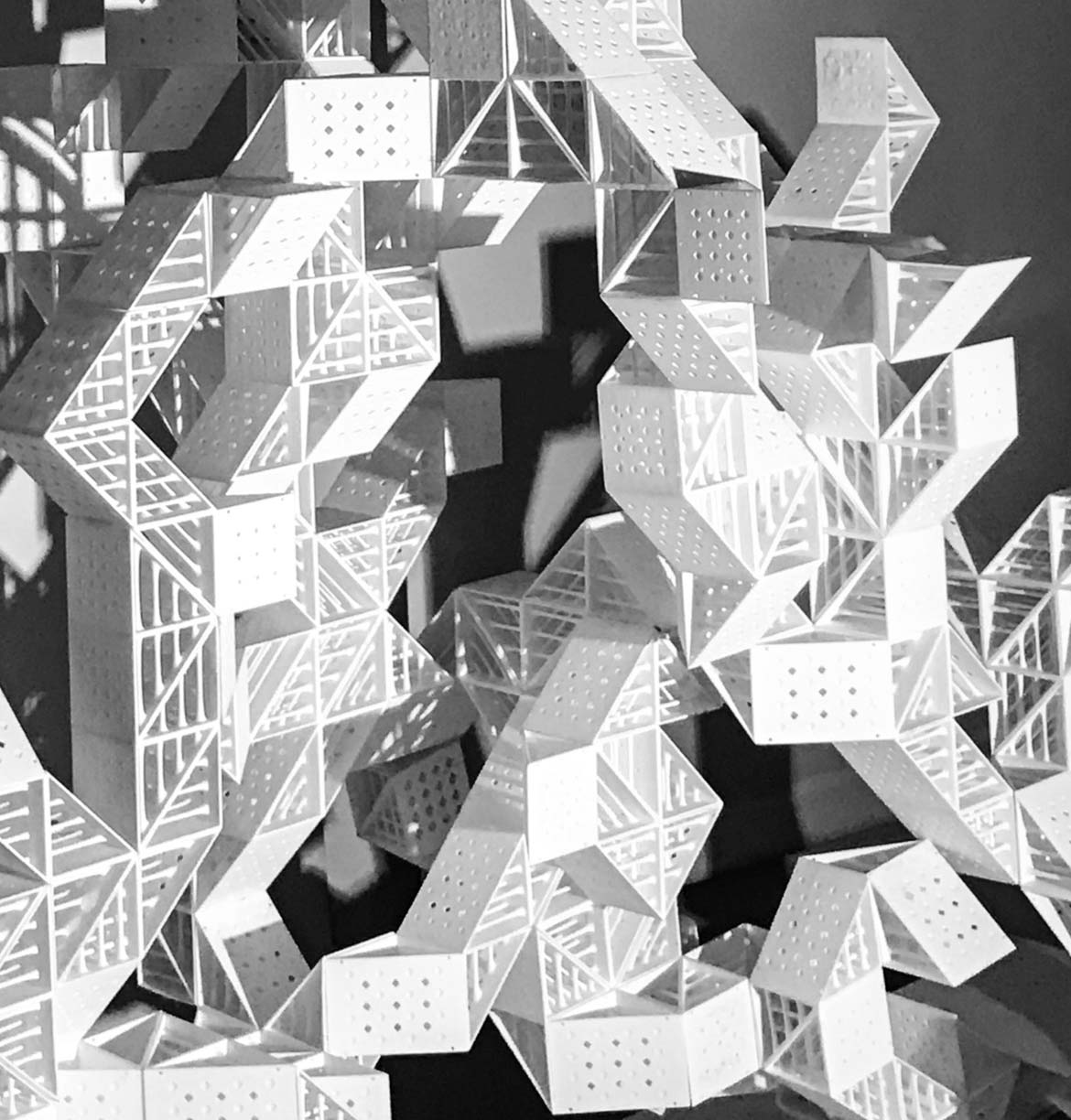

A House: Second Cut

Chapter 3: Domestic Objects

We can blame it on the warmth of summers — on the body’s urge for a cold drink, but an urge that demands style and depicts progressiveness. Sitting out on the terrace, by the pool, a family of four open bottles of fizzy drinks. A bucket of ice is nearby, breaking the unbearable hotness. Pepsi- Cola in hand and icemaker in the kitchen, the family experiences an unforgettable afternoon in the summer of late 1950s Tehran.

Our family afternoon on the terrace is a domestic experience that also unfolds as an urban phenomenon beyond the house — a phenomenon that brings concepts of modern home management into the picture in regards to hygiene, time management and comfort. Coupling ice and refrigerating systems with the automobile industry, supermarkets began to be new spaces in cities; big boxes that had to tear up the urban fabric of Tehran in order to accommodate new liberal lifestyles that required flawless time management. Through the combination of domestic objects and the automobile industry, the domestic realm infiltrated the urban and, vice versa, the city leaked into the house. The city would come to be seen as a continuous fabric of differential intensities, rather than a patchwork of enclosed categories that distinguish between private and public, house and city, or inside and outside. Refrigerators created supermarkets, televisions created cinemas, washing machines created laundrettes, cooking stoves created bakeries, vacuum cleaners sanitized outside spaces, bringing them up to the standard of a well-managed interior. Under the influence of these objects, suddenly, the new city became a projection of domestic life, only bigger. The new city became the ground for leisure and consumption.

-

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 6 (Correspondences)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 6 (Correspondences) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 5 (Publications)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 5 (Publications) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 4 (Photography)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 4 (Photography) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 3 (Domestic Objects)

-

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 2 (Interior Architecture)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 2 (Interior Architecture) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 1 (Architecture & Urban Design)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 1 (Architecture & Urban Design) -

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 0 (Introduction)

A House: Second Cut - Chapter 0 (Introduction) -

No Fixed Adobe

No Fixed Adobe -

GEOtube

GEOtube -

Five Field Play Structure

Five Field Play Structure -

DNAted

DNAted -

Abandoned Qanats of Tehran

Abandoned Qanats of Tehran -

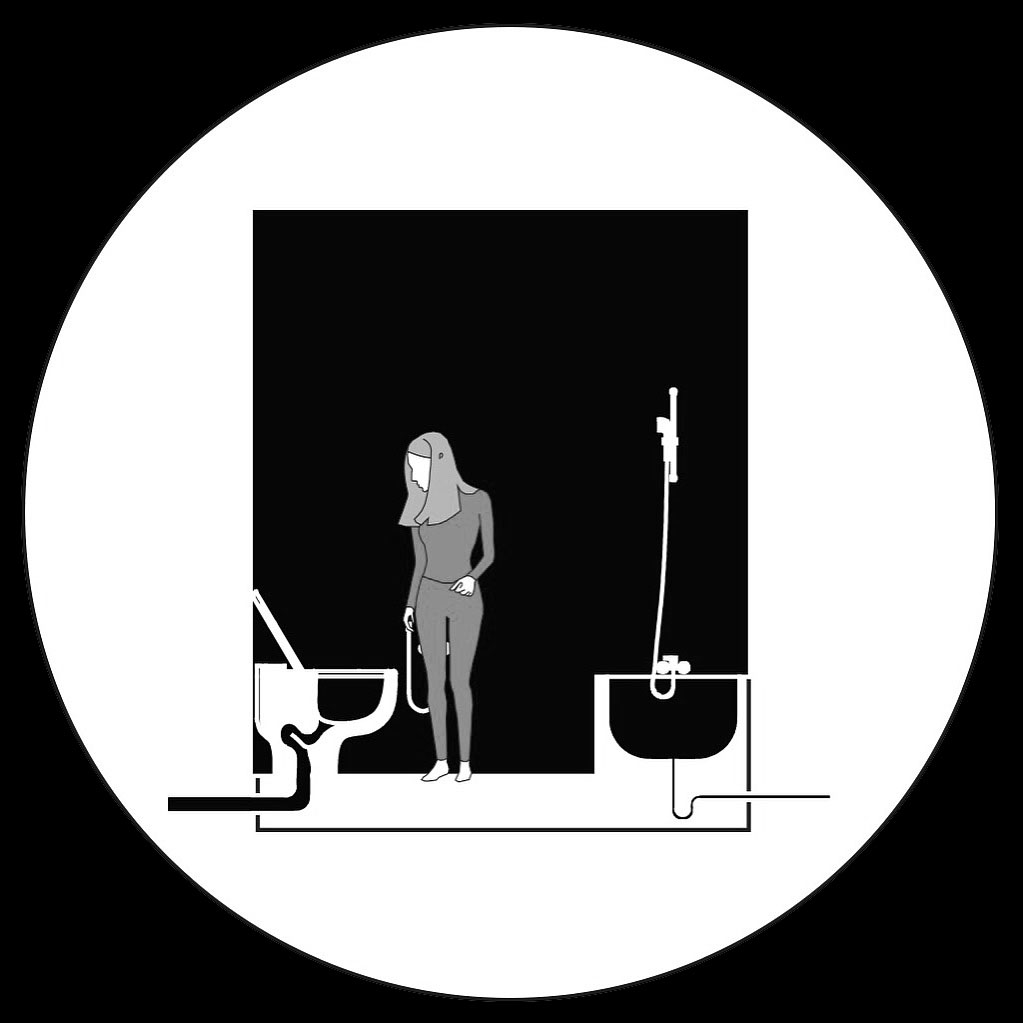

Bathroom Patterns

Bathroom Patterns -

Recycling Socialism

Recycling Socialism -

The delirium of Past and Present

The delirium of Past and Present